One could almost think of musical instrument organology as a Lernaean Hydra, its many necks extending through centuries, its slow movement able to peer around corners in time or see behind multiple walls simultaneously. Mostly, changes in instruments occur outside of human time; however, occasionally, rapid sea changes wash over our multifarious cultures, creating an illusory permanence. The metaphor is perhaps a bit clumsy, but once one begins the fateful journey into organology, the threads and connections which seem to link them dissolve into appendages—faintly connected to a single body. Such is the case with the guitar.

One could almost think of musical instrument organology as a Lernaean Hydra, its many necks extending through centuries, its slow movement able to peer around corners in time or see behind multiple walls simultaneously. Mostly, changes in instruments occur outside of human time; however, occasionally, rapid sea changes wash over our multifarious cultures, creating an illusory permanence. The metaphor is perhaps a bit clumsy, but once one begins the fateful journey into organology, the threads and connections which seem to link them dissolve into appendages—faintly connected to a single body. Such is the case with the guitar.

Although I have been making musical instruments of the Baroque and Renaissance periods for over three decades, whenever anyone inquires which historical period I feel most connected to—and would willingly travel backward to experience and live within—the answer is always, undoubtedly, the 19th century.

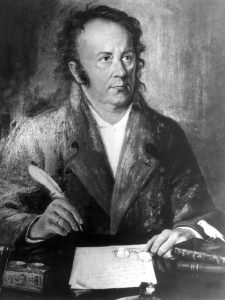

Great and meaningful cultural upheavals were occurring—not only musically, but throughout all branches of the creative arts. The sentiments of Byron, William Blake, and, in Germany, Jean Paul Richter, rebelled against the previous century and a poetical style generally based on odes, epistles, and elegies. Jean Paul (who has always been something of a personal hero) changed German literature so profoundly that one can hardly imagine it without his influence. Although outshined in popularity by the sugary sentiments of Goethe, Jean Paul was the Jimi Hendrix of 19th-century literature. These were portents of a changing century. Great upheavals, inventions, and dreams were soon to spring forth. It is important to see through the looking glass at this tumultuous vision of cultural change, as it generally foretells the transformations soon to come in lutherie.

The Post Baroque Guitar and great innovation.

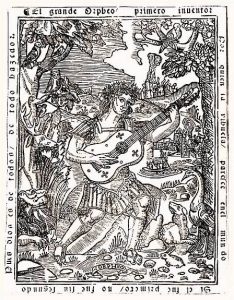

At the turn of the century the guitar in some form had already been in existence for three centuries. The Vihuela, an early ancestor and a “Chistianized” version of the lute, appears in Spain in the 15th Century. Probably due to the influence of bowed medieval viols and fiddles, the bulbous back of the lute is dispensed with.

Guitars made with 5 courses were a French specialty, but were later out of fashion due to the incompatibility to combine with chamber or orchestra.

Violin makers were often tasked with producing multiple types of instruments of different family. In Naples, makers would cater to the musical needs of the public, producing mandolins, and in 1780, Fernando Gagliano working in Naples produced one of the first single string guitars. Unfortunately these instruments were made with very thin, straight backs, and the absence of taped ribs generally led to distortion of the body.

Geigen und Lautenmaker

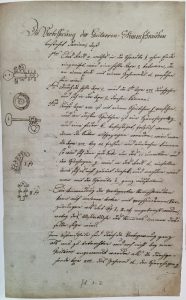

Violin makers and guitar makers today are commonly separated by genus, with one typically not dabbling in the other. This however was not always the case. It was common on violins labels to claim polymathic abilities, even if no lutes were actually produced in the workshop. When one thinks of innovations in lutherie and in Viennese guitars in general, the name Stauffer is usually the first to come to mind. The amount of innovation and bold expiramentation in tone was so great and extensive, as to nearly cause bankruptcy. Stauffer seemed more obsessed with making the perfect instrument than running his business. Many of these changes, such as mechanical tuning pegs, were to precursor the modern guitar as we know it today. Stauffer did not think of himself as soley a guitar maker, though many of his changes were destined to transform the instrument into modernity. Many of his right of privilege claims were for for other instruments, including the pianoforte.

The dual claim printed on the labels, Violin and Lute Maker was occasionally also quite factual.. the list of violin makers who dabbled outside of violin lutherie, who also made guitars, harps. and mandolins, is extensive. Names such as Antonio Stradivari, Joachim Tielke, Guadagnini, Panormo, Lupot, are familiar ones to our ears.

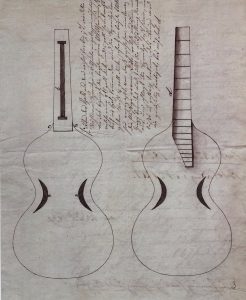

Stauffer was however not alone in his quest. Other Viennese luthiers applied for protection of their innovations, each seeking the elusive dream of the perfect instrument, as well as a technical advantage over the competition.n Peter Teufelsdorfer sought to improve neck stability with the insertion of a steel support rod, a feature still used in modern guitars. One notes in the sound holes a curious relation to earlier bowed instruments, with the form of the body ‘nach Art der Viola d’Amour’ as written in the description.

The “guitarromanie” that swept Europe in the 19th C. was so engaging and overwhelming that many composers of the time could not help but be specks of dust in the broom. in Paris Hector Berlioz used the guitar to compose orchestral music. Other more tender souls such as Franz Schubert used the guitar as compositional tool when writing the monodramatic song cycles, Die schöne Müllerin and the Winterreise. An illuminating quote from the great scholar Phillip Bone sheds some light on these pieces…

“Diabelli published the first compositions of Franz Schubert, when he was unknown as a musical composer, and these first publications were his songs with guitar accompaniment. Schubert was a guitarist, and wrote all his vocal works with guitar in the first instance. Some few years later, when the pianoforte became more in vogue, Schubert, at the request of his publisher, Diabelli, set pianoforte accompaniments to these same songs.” –Phillip Bone

Naturally then there would be some renegades who in the spirit of invention, sought to combine violin family instruments with their plucked cousins. Guitars with violin-like qualitties in the 19th C. seemed to spring forth, (as if another head growing from the Hydra!)

Stauffer developed the Arpeggione in an attempt to combine the dynamic qualities of bowed instruments with guitar construction.

The instrument seemed destined for a bright future, with Shubert composing a Sonate für Arpeggione und Klavier to feature the instrument. Its fate, as was similar to the many heads of the Hydra, was to dwindle into obscurity. Schubert’s sonata in nowadays often performed with a violoncello or viola replacing the curious instrument.

Francesco Molino: The Virtuoso Who Bridged Guitar and Violin

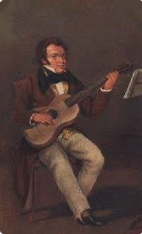

Francesco Molino (1768–1847) was an Italian composer, guitarist, and violinist whose work significantly enriched early 19th-century classical guitar music. Born in Ivrea, near Turin, Molino initially trained and performed as a violinist in orchestras across Italy and France.

Molino had begun oboe and viola studies at age 15, and much of his early life seemed to be devoted to bowed instruments, with employment as a violist in the Royal Theater in Turin 1786-1789. Francesco was something of a polymath, publishing his first violin concerto in Paris, 1803

Molino’s compositions reflect his dual mastery of the violin and the guitar, often blending lyrical expressiveness with technical brilliance. He published numerous guitar works, including solo pieces, duets, and instructional methods. His “Méthode Complète pour la Guitare” remains a valuable pedagogical resource, offering insight into 19th-century performance practice.

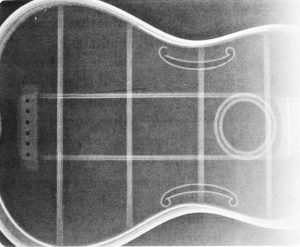

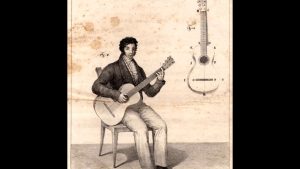

What truly set Molino apart was his inventive spirit. In the early 19th C, he introduced a unique hybrid instrument that fused the qualities of the guitar and the violin. This invention featured a six-string guitar body equipped with elements borrowed from the violin family—most notably, Molino seemed to be speaking to the future when his published his Method. He includes detailed instructions on the parts which compose the instrument, on the fronstpiece in a lovely illustration….

Although Molino’s guitar-violin hybrid never gained widespread popularity, it represented a bold step in instrument innovation. His creation prefigured later efforts by luthiers to expand the expressive range of plucked string instruments. Today, Molino is remembered not only for his elegant compositions but also for his adventurous approach to musical expression.

The arched top and a floating bridge did indeed speak to the future, as these attributes would later appear in modern guitars for the strength, and power of tone. Also unique to the interior construction was the use to two parallel bars, similar to violin bass bars, allowing the maker seemingly absolute control over the projection and tone of the finished instrument.

The Molino model developed by the Mirecort maker, Mauchant Frères, or Mauchant brothers (1762-1844 and 1788-1871), was just this leap ahead that would seemingly form a bridge between the vastly different worlds.

My own fantasy model made in the Spanish workshop takes several flights of fancy, however any deviations were in consideration of tone. The soundhole has been enlarged slightly, and thinner C bout holes employed for a silvery reponse. The pairing of Black Liba and cedar, are by no means kosher, if following our Mirecourt example. But the reward in sound difference is palpable. The finished instrument is a dream to play, and most certainly in the spirit of 19th C invention.

Stay tuned for more wild adcentures in lutherie to come, old friend!