The Lira da Braccio as Fantasy Object

Hyperreality is seen as a condition in which, because of the compression of perceptions of reality in culture and media, what is generally regarded as real and what is understood as fiction are seamlessly blended together in experiences so that there is no longer any clear distinction between where one ends and the other begins – Tiffin, John; Terashima, Nobuyoshi (2005). “Paradigm for the third millennium”. Hyperreality.

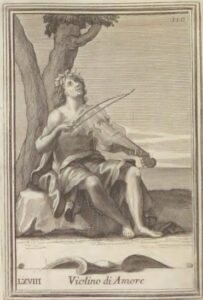

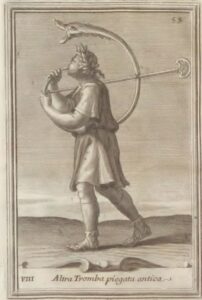

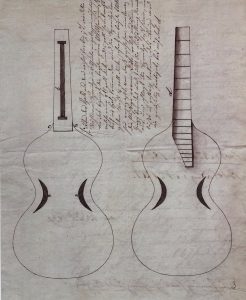

Iconography can provide rich resources into musical instrument contruction when viewed from the proper mind-lens. The majority of these examples however fail to exhibit the level of detail needed to reasonably ascertain their exact contruction, with many images often representing musical instruments which stem from either seemingly near fantasy ideas, phantasmal corpus shapes, right down to facets and traits which are obviously within the realm of the impossible.

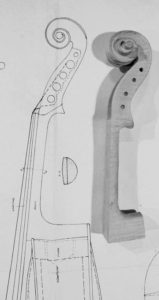

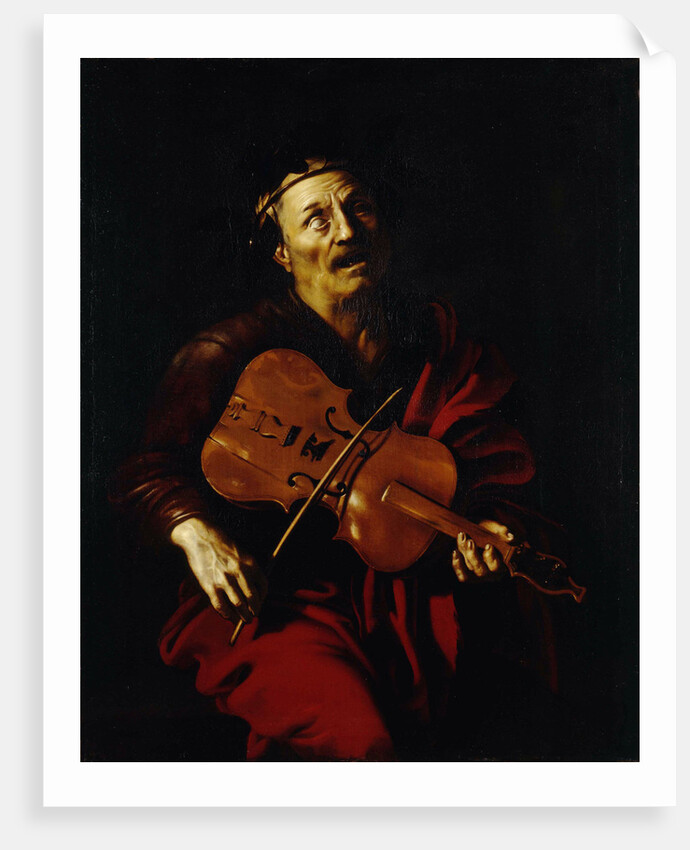

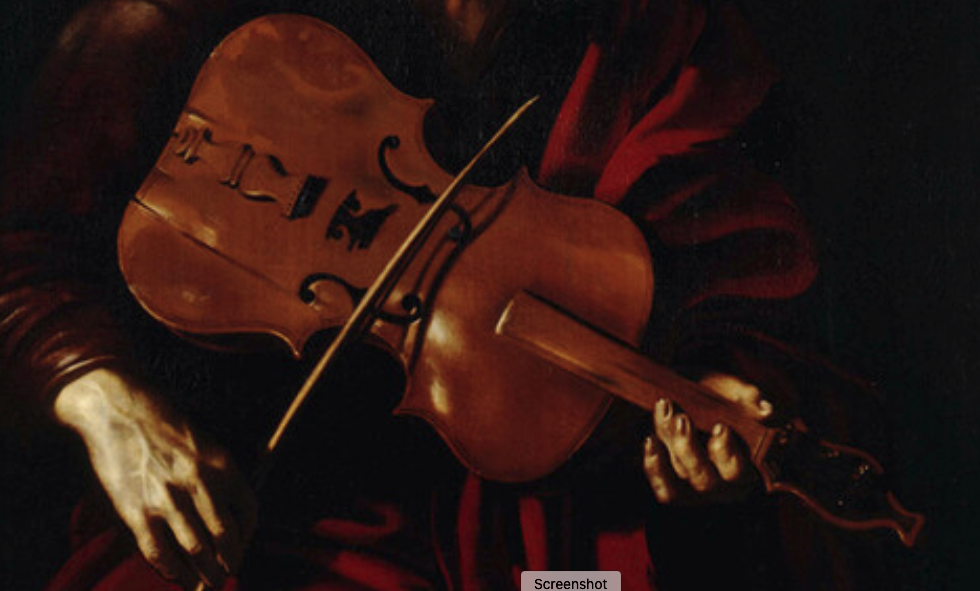

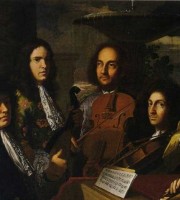

Some works, however, display a breathtaking clarity of detail that leaves little room for doubt, suggesting with high probability that the instruments depicted not only existed, but were likely present as studio props for the artist. In the example above by Nicolas Régnier (1590–1667), Blind Homer Playing the Lyra da Braccio (c. 1622–1623), one can observe extremely fine details that would be implausible as purely imaginary embellishments. The lira da braccio depicted here appears almost exaggeratedly antique. One can clearly discern seven string holes in the tailpiece, now repurposed for use as a tenor viola—a more common configuration at the time.

Specific details such as wear on the fingerboard and abrasion in the varnish where the instrument would have been supported under the chin are clearly visible. One may also note the bulbous arching, finely rendered through the painter’s use of shadow and highlight, as well as a crack extending from the lower waist to the bottom soundhole—a location still commonly prone to cracking today. These details could scarcely be imaginary; and if they were, one must ask what purpose they would serve. While the allegorical context of Homer’s misery may be considered, such varied and technical details appear far more clinical, as though Régnier were simply painting from life.

Another compelling example of this phenomenon of exactitude is found in Willem van Mieris (1662–1747), Serving Maid and Hurdy-Gurdy Player. When one zooms in and focuses on the instrument, the degree of refinement is so extreme that it nearly recalls modern photography.

Note the brilliantly executed wormholes in the lower sections and the chipped tailpiece at the lower corner. Visual portrayals of instruments rendered with this level of detail are priceless to the organologist.

In contrast, other examples blur the boundary between reality and fantasy—either through implausible construction or impossible playing positions. Two important questions to ask when attempting to divine truth from iconography are: Does this image represent an actual historical moment? and Was an actual instrument present at the time of painting? One may argue either in the affirmative or the negative. Often, however, the painter’s original context and intent remain elusive, and the modern eye—inclined toward categorization and compartmentalization—can fall short.

In cases where the intent is undoubtedly allegorical, such as the early pilaster carving representing Thalia holding a viola da braccio, the limitations of the medium and the utilitarian economy of its purpose become evident. Such carvings may have adorned beds, cupboards, chimney-pieces, or overmantels, where symbolic clarity outweighed structural accuracy.

Iconographic examples are so numerous that it would be both impossible and superfluous to include them all here. Levels of accuracy oscillate wildly—from the absurdly implausible to depictions of such extreme fidelity that they leave little doubt as to the instrument’s real existence.

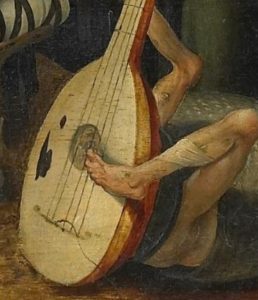

Many examples omit the depiction of drone strings altogether. In the example above, however, we see the technical detail of strings being fed into a hidden chamber and attached to internal pegs. This feature lends further credibility to the idea that the instrument was physically present during the painting process, rather than existing solely as a figment of imagination.

Whimsical Renaissance and the Fantastical in Lutherie

Leonardo da Vinci’s Mythical Horse-Skull Lira da Braccio

My first exposure to Giorgio Vasari’s engaging Lives of the Artists (Le vite de’ più eccellenti pittori, scultori e architettori, 1568) occurred when I was a young teenager. Reading these volumes alongside my pocket-sized Loeb translations—bound in faded red cloth—I felt transported into history, able to explore the lives of my heroes with little detail spared. The work is both illuminating and entertaining, though, as with Herodotus, one must rely on modern interpretation and historical criticism: Vasari was notably prone to reproducing tantalizing fragments of gossip and legend.

Nevertheless, his coining of the term rinascita (“rebirth”) comes surprisingly late, considering the sweeping creative changes already underway. It is, of course, well known that Leonardo da Vinci devised numerous fantastical instruments, many of which have been reconstructed by modern scholars with varying degrees of success. One particular story recounted by Vasari is too fascinating—and too relevant—to pass over.

According to Vasari, Leonardo brought with him to Milan an unusual lira da braccio of his own making—“in great part of silver, in the form of a horse’s skull”—designed specifically to produce a resonance louder and more sonorous than that of ordinary instruments. This bizarre and novel creation captivated the ducal court and allowed Leonardo’s performance to surpass that of the other assembled musicians.

According to Vasari, Leonardo brought with him to Milan an unusual lira da braccio of his own making—“in great part of silver, in the form of a horse’s skull”—designed specifically to produce a resonance louder and more sonorous than that of ordinary instruments. This bizarre and novel creation captivated the ducal court and allowed Leonardo’s performance to surpass that of the other assembled musicians.

Whether this tale is one of Vasari’s colorful embellishments remains debatable. What is clear, however, is that the broader cultural impetus of the period was moving toward a neo-humanism inspired by classical Greek literature. This movement influenced all branches of creative endeavor. Although these intellectual currents were often sober and grounded in devout reflection, the whimsical spirit of the human mind could never be fully suppressed.

In iconography alone, hundreds of fanciful representations—from the whimsical to the unabashedly vulgar—may be found with even the briefest perusal.

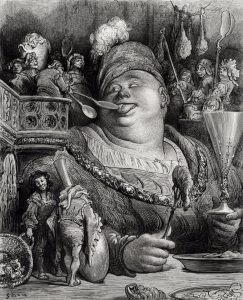

In literature, the grotesque realism of François Rabelais uniquely merged the vulgar and the elegant in the expression of humanist ideals. He opens the prologue of Gargantua and Pantagruel with a striking dedication:

“Most illustrious drinkers, and you the most precious pox-ridden—for to you and you alone are my writings dedicated …”

Rabelais’ work reflects the spirit of carnival—an antithesis to devout perfection—at a time when French writers were beginning to question the soundness of papal authority.

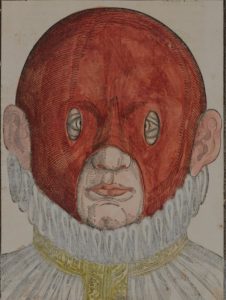

The Lira da Braccio as Anthropomorphic Fantasy

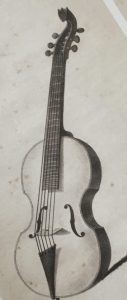

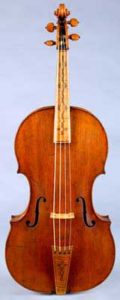

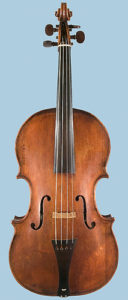

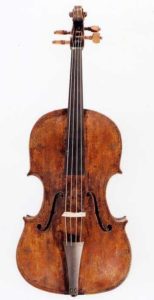

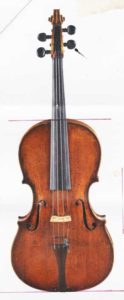

The lira da braccio by Giovanni d’Andrea (1511) provides a surviving example of this playful spirit, both in its composition and its ornamentation. Wherever one’s gaze falls, the wonders of a curiosity cabinet seem to lure the eye and imagination ever deeper, as though the instrument itself were a living creature. The many phantasmal and anthropomorphic features, along with the carved back, reinforce the idea that this is an instrument intended for musicians and poets alike.

Although later research may cast doubt on the authenticity of all its components, the instrument’s existence reaffirms a playful spirit in lutherie that is largely absent from modern lutherie.

Distortions of size and perspective, instruments held by demons, angels, or animals, and improbable playing postures appear repeatedly throughout history. Even in the pursuit of truth—when one seeks the most clinically accurate depiction—one may still find oneself within a realm of fantasy. Bonanni, Kircher, and the conception of the organologist as mathematician connected to the cosmos all reflect this tension.

Bonanni, Kirchner, The Organologist as Mathematician connected to the Cosmos.

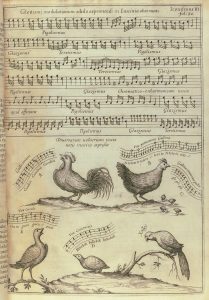

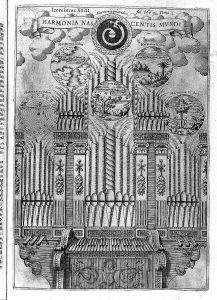

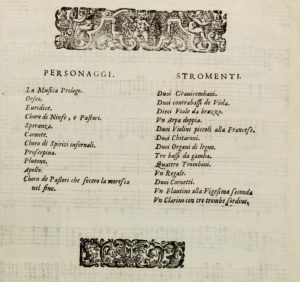

Leonardo’s horse-head lyra was but one invention among a well-documented multitude. The fantastical conception of sound-producing machines continued forward through time, pressing the limits of human imagination. In 1650, the polymath Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher published his vast and esoteric Musurgia Universalis, sive Ars Magna Consoni et Dissoni (“The Universal Musical Art, or the Great Art of Consonance and Dissonance”). Printed in Rome in two lavishly illustrated volumes, the work preserves invaluable visual and technical evidence of early Baroque instruments that might otherwise have been lost.

Musical Instruments in Musurgia Universalis

Kircher’s discussions of instruments appear throughout the text—most vividly in the engraved plates that depict stringed, wind, and keyboard instruments. These illustrations, alongside his descriptions, serve as early attempts at a systematic organology, predating later standard works in the field. The plates include representations of harpsichords, organs, and a variety of stringed and wind instruments, all rendered with attention to structural detail and tunings (which often err!). though Kircher has borrowed or copied exactly from Mersenne, his approach and mindset is completly unique.

The ten sections are divided into an astonishing array of subjects, in book one a diverse treatise on the sounds made by animals, birds and insects, the philogical orgin of sound, anceint Greek and Hebrew music, and the magic of consonance and dissonance and their effects on the mind and body.

the philogical orgin of sound, anceint Greek and Hebrew music, and the magic of consonance and dissonance and their effects on the mind and body.

The roughly two dozen engraved plates in Musurgia Universalis show not only instruments but often constructional details and proportions, linking them to Kircher’s wider theories of harmony and acoustics.

In contrast to contemporary paintings, where a musical instrument was merely a prop, or serevd an allegorical significance, Kircher’s use of visual imagery was not merely decorative; diagrams illustrate his belief in the deep connection between mathematics, physical acoustics, and musical practice. Instruments were visualized not only as objects but as embodiments of cosmic harmony—appearing alongside symbolic woodcuts and diagrams that link music to cosmology. Like Mersenne, Kircher’s impetus sought to tie the physical world and a-priori perception as proof of divinity, with the diisonante facets of sound connected to the universal presense of evil in the world.

n one section, Kircher quite literally binds instrument construction to divine creation, using a six-register organ as a metaphor for the six days of creation—uniting musical harmony and theology into a single concept.

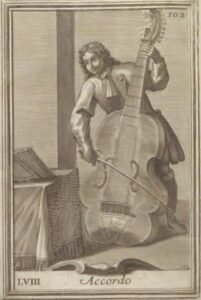

Kircher’s text on the creation of viols and lutherie is particularly interesting as it gives a very clear portrait of the wide diversity and chronic invension, innovation, and creativity amoung his contemporaies, depicting a kind of wild west of lutherie which was rampant across the globe.

By viol is understood that instrument that consists

of belly and neck or fingerboard, and which is sounded with a

plectrum or bow made of horsehair, the left hand grasping the

neck, and its fingers pressing the strings directly. But

there is such a variety of these instruments, that whoever

lists the customs of the various nations, will also list a

corresponding variety of viols. For in this so learned age,

almost every craftsman invents viols of new designs. Some

add strings to strings; some design them in the fashion of

lyres, and there is no lack of those, such as the English,

who construct them partly with metal strings and partly gut

for greater variety. Whoever desires to know exactly the

uses of all of them, should read here Pere Mersenne, who

treats of them with variety and erudition in a whole work.

Kircher goes on to reference Giovanni Battista Doni—a contemporary of Galileo and scholar of ancient music—who devised a curious double lyre inspired by the ancient Greek barbiton. He also mentions the Lyra Barberina, Doni’s Panharmonic Viol, Cerone’s Lyra Argolica, and the extraordinary diversity of tunings and constructions found across Europe.

Bonanni’s Organology in the Context of Kircher’s Vision

Kircher’s influence on Bonanni extends beyond direct mentorship to a broader cultural aesthetic. In works like Musurgia Universalis, Kircher treated music as a universal art, connecting the mathematical properties of sound with cosmic harmony and spiritual meaning.

Bonanni’s organological project inherits this integrated worldview: instruments are not merely cataloged as curiosities but are situated within realms of ritual, ceremony, war, religion, and daily life. The very title Gabinetto Armonico evokes the “cabinet” — a curated space where objects both educate and astonish, where the sensory encounter is itself a form of knowledge.

While later commentators have noted inaccuracies in some of Bonanni’s representations and attributions, Gabinetto Armonico remains indispensable for the history of musical instruments. It stands as one of the earliest comprehensive illustrated guides to the organological world, influencing later surveys and histories.

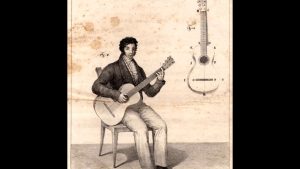

While the lira da braccio itself had long since disappeared as a common instrument by the 17th century, its structural and conceptual legacy lived on. The visual lineage from Renaissance bowed instruments to the modern violin family is reflected in shape, playing posture, and tuning approaches. Over the 17th–19th centuries, the violin family matured into the iconic instruments we know today — shaped by musical tastes, performance demands, and the evolving art of lutherie. I add these word simply wishing to move forward.

The story is not one of a simple, singular transformation of existing instruments into violins but of a continuum of bowed instrument design in Europe. From Byzantine and medieval bowed instruments through Renaissance lira da braccio and viola da braccio types, to the refined violin family of the Baroque and onward, we see a cultural and technological evolution grounded in both artistic and acoustical innovation.

New inventions in lutherie today are even less common not for the nature of the human mind becoming stagant, but for a cultural dogmatism grounded in a limited and myopic aestheic for tone which seems to be arrested in the 19th Century. If my call for more poetry, more invension, more daring and rebellous spirit goes unheeded in future lutherie, I can, at the very least, take solace in the fact that I spoke at all.

to better accocopany the cacaphonic screeching of bel canto opera in the 19th. Century.

to better accocopany the cacaphonic screeching of bel canto opera in the 19th. Century.

One could almost think of musical instrument organology as a Lernaean Hydra, its many necks extending through centuries, its slow movement able to peer around corners in time or see behind multiple walls simultaneously. Mostly, changes in instruments occur outside of human time; however, occasionally, rapid sea changes wash over our multifarious cultures, creating an illusory permanence. The metaphor is perhaps a bit clumsy, but once one begins the fateful journey into organology, the threads and connections which seem to link them dissolve into appendages—faintly connected to a single body. Such is the case with the guitar.

One could almost think of musical instrument organology as a Lernaean Hydra, its many necks extending through centuries, its slow movement able to peer around corners in time or see behind multiple walls simultaneously. Mostly, changes in instruments occur outside of human time; however, occasionally, rapid sea changes wash over our multifarious cultures, creating an illusory permanence. The metaphor is perhaps a bit clumsy, but once one begins the fateful journey into organology, the threads and connections which seem to link them dissolve into appendages—faintly connected to a single body. Such is the case with the guitar.

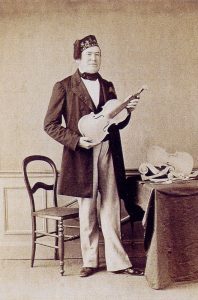

The moniker comes most certainly from the Odori of the wood, which blossoms and is magnified greatly when carved. Cedrela is actually related to the mahogany family of woods, however, is infinitely softer, and lighter in weight. Colichon without question had a very strong intuitive force in imagining the tonal capabilities of this unique material, as he used it for the tops of his instruments, not only the back and ribs. A completely radical experiment in the history of lutherie. His intuition proved correct. All of the Viols made entirely of Cedrela are famous for their very fine tone.

The moniker comes most certainly from the Odori of the wood, which blossoms and is magnified greatly when carved. Cedrela is actually related to the mahogany family of woods, however, is infinitely softer, and lighter in weight. Colichon without question had a very strong intuitive force in imagining the tonal capabilities of this unique material, as he used it for the tops of his instruments, not only the back and ribs. A completely radical experiment in the history of lutherie. His intuition proved correct. All of the Viols made entirely of Cedrela are famous for their very fine tone.

Now imagine you have been given the magical power to change the composition of the surfaces. In the ceramic room, sounds from your voice reflect very quickly back to the ear, and the timbre of sound is something easily imaged. Now you change the surface commotion to steel, tin, or brass. The sound reflection changes as does the actual timbre and character of sound. A softer surface such as leather, would dampen the sound, and even softer such as foam insulation, would kill the reverberation entirely.

Now imagine you have been given the magical power to change the composition of the surfaces. In the ceramic room, sounds from your voice reflect very quickly back to the ear, and the timbre of sound is something easily imaged. Now you change the surface commotion to steel, tin, or brass. The sound reflection changes as does the actual timbre and character of sound. A softer surface such as leather, would dampen the sound, and even softer such as foam insulation, would kill the reverberation entirely.

A very finely made instrument will sound terrible if the bridge is not right. The problem with this approach is that modern, factory bridge blanks are often made from kiln-dried, or even chemically treated wood. In the past, more organic solutions such as animal urine were used to ammoniate and hence harden the wood stock, the theory being that this would be easier to cut, and produce a clearer sound.

A very finely made instrument will sound terrible if the bridge is not right. The problem with this approach is that modern, factory bridge blanks are often made from kiln-dried, or even chemically treated wood. In the past, more organic solutions such as animal urine were used to ammoniate and hence harden the wood stock, the theory being that this would be easier to cut, and produce a clearer sound.

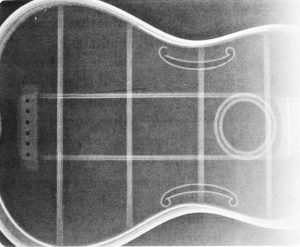

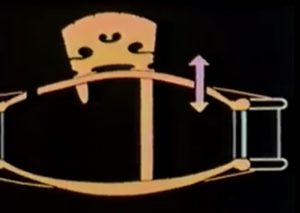

A rocking motion is formed by the vibration of the strings, which in turn forces air and sound outwards through the soundholes. The feet are supported by both bass bar and soundpost, otherwise, the top would collapse and shatter from the pressure of the strings. Usually, by “tuning” the heart and kidneys, the maker searches for optimum sound.

A rocking motion is formed by the vibration of the strings, which in turn forces air and sound outwards through the soundholes. The feet are supported by both bass bar and soundpost, otherwise, the top would collapse and shatter from the pressure of the strings. Usually, by “tuning” the heart and kidneys, the maker searches for optimum sound.  I begin with a stock of bridge wood aged over 20 years in my workshop. One can see the patina of age and know from tap testing that this wood stock was ready long ago. The more time however, the better. Wood looses moisture over time. When you examine the rays of the wood, one can get a sense of the density needed to be a violoncello bridge

I begin with a stock of bridge wood aged over 20 years in my workshop. One can see the patina of age and know from tap testing that this wood stock was ready long ago. The more time however, the better. Wood looses moisture over time. When you examine the rays of the wood, one can get a sense of the density needed to be a violoncello bridge

This bar essentially stops the pressure of the strings from expanding the bridge feet when on the instrument, and also acts as a (perhaps!) desirable damping mechanism.

This bar essentially stops the pressure of the strings from expanding the bridge feet when on the instrument, and also acts as a (perhaps!) desirable damping mechanism.

It would be an additional 10 years before I finally got to that particular piece of maple.

It would be an additional 10 years before I finally got to that particular piece of maple.

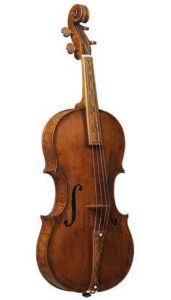

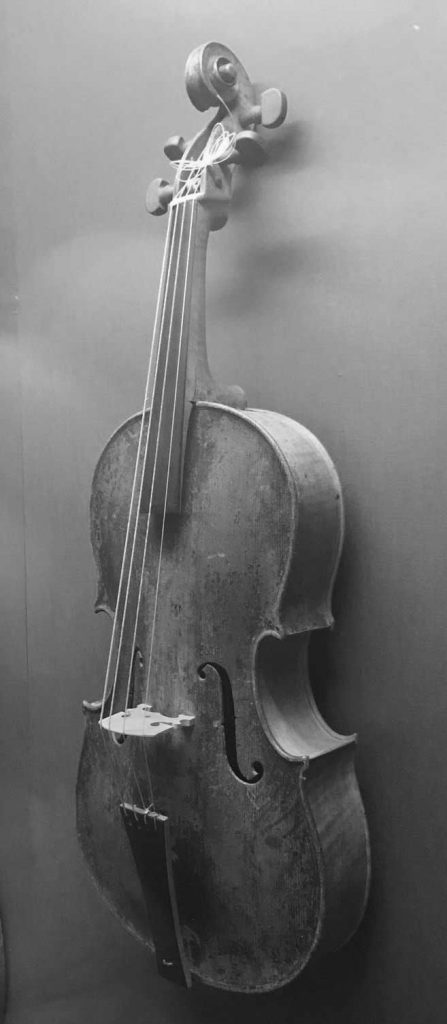

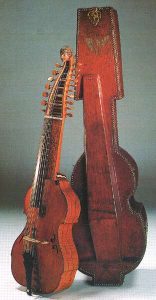

Thankfully, the instrument survives in a remarkable undamaged state, including its charming original case of red leather, in the Hugarian National Museum.

Thankfully, the instrument survives in a remarkable undamaged state, including its charming original case of red leather, in the Hugarian National Museum.