When one looks for a solution within the facets of history with a particul;ar gem already in mind, behind every curtain and inside of every shadow, one will see riches. The mind colors substance to suit its needs, desires, and dreams.

While researching for the previously written tenor viola blog and attempting to catalogue as many tenor violas as the documentary record will surrender—a seemingly endless and fruitful task—I began, quite simply, to see them everywhere. “I see dead people,” as the famous line goes.

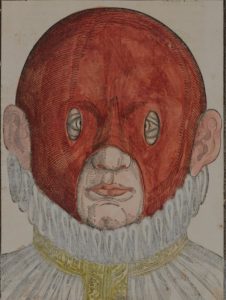

The specific organological question of the composition, structure, and even the tuning of the many viole da braccio referred to in countless partbooks and scores through the centuries remains a contentious and unresolved conundrum. Iconography is, unfortunately, of some but little help. Taking images as literal truth rather than cum grano salis can result in particularly terrible designs—one need only Google “viola da braccio” to witness the cartoon show of instrument caricatures produced by what may be honest-hearted woodworkers, albeit with a pen inclined to draw a nose larger than life. The tonal spectrum, as reflected in the composition of the instruments, can be much easier surmised when evaluating historical instruments, together with a careful analisis of iconographical images. Suddenly, the myopic, 21st C mind may with some luck, be able to grasp a phantasmal concept of sound.

The earliest recorded use of mahogany in Europe appears in the construction and furnishing of King Philip II’s Escorial Palace, completed in the 1580s. Yet Spanish colonists must have recognized the remarkable properties of this New World timber much earlier. A mahogany cross documented in Santo Domingo as early as 1514 stands as evidence that the wood’s durability, resistance to decay and insects, and its almost divine perfume when carved were noted from the very first decades of contact. It is fitting that such an “immortal” wood was first used for a sacred object.

The Spanish and Portuguese crowns, having framed their overseas expansions as spiritual “crusades” against unbelief as well as imperial quests for wealth, relied heavily on timber—both at home and abroad. By the mid-16th century, Spain faced a precarious imbalance: its native forests were insufficient to sustain the massive shipbuilding industries required for military, religious, and commercial ambitions. Philip II, acutely aware of this, instituted ordinances requiring two trees to be planted for every one felled—an early, if imperfect, gesture toward conservation.

Portuguese acquisition followed a similar trajectory. Their holdings in Brazil—where the closely related species Cedrela odorata (Spanish cedar) and several Swietenia species grew abundantly—made Lisbon an early European center for exotic hardwoods. Portuguese shipwrights, furniture makers, and instrument builders quite possibly had access to these materials long before they became fashionable in the rest of Europe.

By the late 17th and 18th centuries it had become on of the dominant luxury woods in the Anglophone and Iberian worlds—so much so that British and American colonial elites used it as a conspicuous marker of wealth.

Given this flourishing trade, it requires little imagination to assume that boards of mahogany, cedar, and various tropical hardwoods filtered into the hands of luthiers. With Spain and Portugal effectively cut off from the Silk Road and the Venetian luxury markets after the Ottoman ascendancy, the Atlantic became the more attractive route for the accumulation of raw materials—and mahogany arrived in Europe quite literally as part of the spoils of empire.

Locally sourced tradewoods such and pear, plumwood, and yes even apple – nutwoods such as walnut were very common. Anything one can lay hands on, would be the general impetus.

Early Examples: Cedar and Fruitwoods in Luthiery

One of the clearest documented examples of a cedar–fruitwood pairing appears in the lyra da braccio of Francesco Linarol, Venice, 1563. Its curious rib garland, carved from a single piece of pearwood, surrounds a voluminous corpus nearly 50 cm in length. Such combinations were far from unusual in the 16th century, especially before the later “standardization” of violin-family woods.

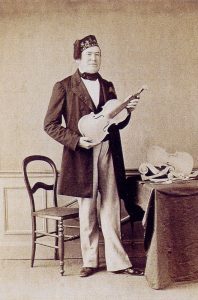

No less a maker than the great Jakob Stainer—who held a leading reputation as the world’s greatest violin maker—used fruitwoods for two esoteric Armviolen, commissioned by the archbishop of Salzburg for the court chapel. Note also that the rather massive corpuses fit our imaginary tonal portrait assosiated with both iconography of viole de braccio and surviving instruments. Here again we see the typical viol construction using plum and bird’s-eye maple in joined strips, with arched spruce tops, usually Haselfichte, characteristic of the Northern Alpine and Füssen makers who migrated to Venice in search of their fortunes.

One of these instruments shows the typical rib-depth reduction intended to conform to more 19th-century playing requirements, and both necks have been thinned or lengthened with this aim. We have further tangible proof of Stainer’s use of exotic woods in a letter promising the delivery of a viola da gamba made with Indian woods, and requesting payment in cash.

Michel Colichon and the Maverick use of hardwood for soundboards

The most famous example of the use of Cedrela odorata, or Spanish cedar, comes of course from the now-legendary viols made by Michel Colichon, whose tone has been revered for centuries. His bold and unique use of cedrela for the top plates was a particularly maverick endeavor, given the lack of historical precedent for deviating from the customary spruce tops. The resulting tone is completely unique, given the damping qualities of Spanish cedar deliver a more silvery, deeply rewarding response. One need only to rememeber how original was this leap into tonal expiramentation given that the moniker Spanish Cedar, actually referes to a hardwood, mahogony, albeit a softer species. Other hardwoods such as cypress have been used for the soundboards of harpsichords, though spruce of course was much more common.

Indeed, when browsing the instruments presented on my website, you may notice a unique trend. Look carefully and observe the absence of the more traditional 18th-century pairing of maple and spruce. Picea abies (spruce) and Acer species (maple) eventually became the normative materials for violin-family instruments, but this was not necessarily a boon for lutherie. In fact, this narrow, myopic limitation has plagued violin making since the 19th century and continues to this day.

This pairing tends to produce a clear, powerful projection—qualities prized by 19th-century concert culture—but it also homogenizes tone in ways that reflect the tastes of that period rather than the rich diversity of earlier practices. These ideals were later amplified—one might even say distorted—by the opinions of a few rather unscrupulous dealers and marketeers.

Charlatans such as Jean-Baptiste Vuillaume were not only seeking gain when perpeuating the false Strad Mythos, but also rampantly involved with the butchering of Cremonese violins  to better accocopany the cacaphonic screeching of bel canto opera in the 19th. Century.

to better accocopany the cacaphonic screeching of bel canto opera in the 19th. Century.

As with the Stainer Armviolen above, the original tonal intent is somewhat mystifying to imagine, given our modern ear and the jaded mind it is connected to, but one can easily surmise the more softer aestetic by listening to performances using all gut stringing. The difference is profound.

Monteverdi and his ten voices for profound expression

But I most certainly do not wish to say that our tonal portraits in sound should be whispery, softer spoken cousins to their hacked down counterparts…Monteverdi would have demanded powerful and potent instruments to accopany his radical new idea of Opera, ones which would not be lost among the voices of the other instrumentation.

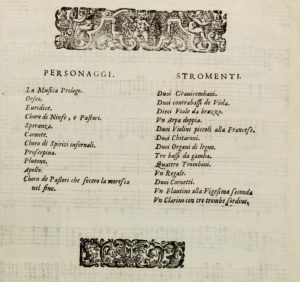

In L’Orfeo (1607), Monteverdi’s request for Dieci Viole da Brazzo is striking and highly purposeful. Rather than functioning as a uniform string section in the later Baroque sense, these instruments are used flexibly to color scenes, support text delivery, and help delineate emotional and dramatic contrasts throughout the opera. Monteverdi exploits their warm, human-voiced timbre to mediate between speech-like declamation and fully lyrical singing, making them ideal partners for the evolving vocal styles of the work. Whether or not the instrumentation simply means ten bowed instruments is a point of contension, as beyond the rather limited information we can gain from Praetorius writings, our knowlege is limited as to the use and even the tunings of these instruments.

One facinating theory by Ben Hebbert is highly worthy of consideration, though admittedly a musing, purports to say that the term viola da braccio and the confusion around it over the centuries is merely a semantic issue clarified at once with the assumntion that Brazzo, and Gamba, were simply usits of measure in the Renaissance mind. This does hold firm given the myriad of names given for esoteric deveations in stringed instruments in general. Read on further here.

If were are then to take Claudio´s desires stright from the horses mouth and assume he quite simply litterlly meant ten viola da braccio then an entire world of performance does seem to spring forth, and this is one not yet fully explored in contemporary performance.

For example, in passages of recitative, such as the Messenger’s devastating narration of Euridice’s death (“In un fiorito prato”), the violas often provide sparse, sustained harmonies or simple chordal support. Their restrained use allows the text to remain at the forefront, intensifying the rhetorical delivery and heightening the sense of shock and inevitability. The blended sound of multiple violas creates a darkened, veiled sonority that mirrors the emotional gravity of the moment without drawing attention away from the words.

By contrast, in more arioso passages—most notably Orfeo’s lament “Tu se’ morta”—the violas assume a more expressive role. Here they reinforce the melodic contours of the voice, sometimes moving in gentle counterpoint or providing richer harmonic padding. The collective weight of the ten instruments lends gravity and depth to Orfeo’s grief, transforming the lament into a moment of suspended time. The violas’ close relationship to the human vocal range makes them particularly effective in conveying intimacy and emotional vulnerability.

In the more aria-like sections, such as Orfeo’s opening song “Ecco pur che voi ritorni,” the violas contribute to a brighter, more animated texture. They may be divided into smaller groups, creating antiphonal effects or rhythmic vitality that complements the dance-like character of the music. In these moments, the violas participate in the celebratory atmosphere of the pastoral world, reinforcing its balance, warmth, and order.

Monteverdi also uses the violas in madrigal-style choral passages and instrumental interludes, where their number allows for rich polyphonic writing. These sections recall the composer’s roots in the late Renaissance madrigal tradition, while simultaneously pointing toward the emerging operatic idiom. The violas act as a sonic glue, unifying voices and instruments and smoothing transitions between scenes.

Just as important is the way the viola ensemble interacts with the basso continuo, which changes according to dramatic context and character. Monteverdi provides unusually specific instructions in the score, assigning particular instruments to particular situations—an innovative practice at the time. Elevated, “noble” instruments such as the harp, chitarrone, and harpsichord are associated with pastoral scenes and divine characters, while darker, lower-pitched continuo instruments, including the regal organ, dominate the underworld scenes. Against these shifting continuo colors, the violas function as a constant expressive middle ground, capable of reflecting both earthly sorrow and lyrical beauty.

Based on Monteverdi’s indications and contemporary practice, if we assume that the orchestra for the first performance of L’Orfeo consisted of a varied ensemble including ten viola da braccio, with the violins piccolo, violone, multiple continuo instruments (harpsichord, organ, regal, chitarrone, harp), cornetts, trombones, and recorders. The prominent role of the viola da braccio group underscores Monteverdi’s concern with instrumental color as a vehicle for drama, emotion, and meaning—anticipating the orchestral thinking of later opera while remaining rooted in Renaissance expressive ideals.

Remembering that these gut-strung instruments, when combined, would have possessed not only considerable power but also a remarkable immediacy of response, one gains a clear sense of the striking contrast with many modern performances that rely on wound strings. The earlier sound world was at once direct, resonant, and uncompromising in its presence.

Flat-back construction offers a dramatic alternative to arched, carved backs. Acting almost as a second soundboard, the flat back serves both to amplify and to reflect sound. While this approach may appear more limited in terms of graduation, the introduction of internal bracing opens an expansive field of possibility. Here, the luthier seems almost to grow wings. Variations in damping, distribution, and the very composition of bracing materials are virtually inexhaustible. Roger Hargrave, when addressing the question of bracing, has described the multitude of historical approaches as nearly mythical in character. Indeed, makers often speak of this process with such intensity that it borders on the alchemical; the shaping of sound becomes a pursuit that edges toward the mystical.

Moving further toward a more reflective, silky, yet powerful tone, the use of woods such as Swietenia, Cedrela, walnut, and other materials beyond the narrowly conceived eighteenth-century spruce–maple pairing seems not only logical, but entirely natural. If the pursuit of tone leads to hidden treasures, they are not always easily uncovered. One must sometimes take great leaps, uncertain whether the ground beneath will prove firm, or whether one will instead be carried away into an endless sea of sound.