Most violists are familiar with the contemporary tenor size viola and its stark contrast to the historical Baroque tenor viola. In relation to this modern mindset in which a scale of corpus reaches a maximum of 43cm or (17″) all aspects of the construction of these utterly modern violas, their string and neck lengths, mensur, and ribs depths, are usually set by the standards of the Quaderni di Liuteria and dimensions taken from Cremonese instruments altered in the 19th Century. It is no small wonder then that they will often add the notion that they are unplayable, giant beasts, ill-suited for day-to-day playing and most repertoire.

Many however fail to grasp that the ergonomic design of historic large tenors made them quite manageable as compared to the modern tenor. Overly large violas and their players in contemporary culture and particularly in the 20th Century, have been the subject of unfair discrimination and jesting, humorously seen as a knuckle-dragging curmudgeons unable to manage the virtuosity needing for modern violin performance. On the other hand, 20th Century violin makers began to realize and recognize that the sonority of the larger corpus violas was something greatly desired, or even aesthetically more pleasing than the smaller alto or contralto sized instruments.

The tenor viola has a dark past. As if a hunted beast, most were “cut down” in the 19th Century to make smaller instruments. These hacked-down specimens regularly come up for auction as crippled versions of their old larger selves. The most obvious sign that they were once larger instruments is wide sound hole spacing close to the purfling or outline. Less often noticed or remarked upon is the practice of rib reduction. Often, this butchery is done so well and convincingly, that modern eyes fail to see the changes. The alteration of musical instruments did not begin only in the mid to late 19th Century as a means to turn a profit, however. The workshop of the Mantegazza family of violin makers was entrusted with the regraduation and thinning of many of Guarneri del Gesu’s violins. The voice of your favorite Del Gesu violin would probably not even be recognized by its creator should he magically be able to listen to it today. With the successive generations around1800 (likely prompted by the violinist Viotti) the workshop was one of many who were involved in altering/lengthening necks to modern dimensions. Neck blocks were added as a necessity towards a mortised, not nailed, neck. It may surprise you to know that the majority of all violin makers working today reproduce these 19th Century alterations when they make an instrument. In effect, they reproduce a sound and tone which were not by any means the intention of the luthiers they seek to emulate. The “Strad Cult” is another topic altogether, as is the emergence of 19th C. Opera, which was the beginning of the total destruction of the culture of artisenal, handmade keyboard instruments in Italy. For now, we will focus on violas.

The early tenors were often massive instruments with back lengths at 50cm and occasionally, even larger. What is often overlooked is that in Italy the neck lengths were commonly made at around 12cm, or shorter than our modern violin neck. Playing postures varied considerably and were both under the chin and rested on the arm. In the Organological treatise of Praetorius Syntagma Musicum, written in 1618, two separate tunings are given for the Tenor Geige – the instrument which corresponds to the larger tenor violas. One may note that the rib depth is quite substantial; a characteristic trait that would continue in the construction of later tenors far into the 18th Century, some of which will be seen below. These instruments must have been massive. The position of the instrument resting on the arm was likely much more common than one would assume, as ribs depths and corpus most certainly made them difficult to be played under the chin.

The early tenors were often massive instruments with back lengths at 50cm and occasionally, even larger. What is often overlooked is that in Italy the neck lengths were commonly made at around 12cm, or shorter than our modern violin neck. Playing postures varied considerably and were both under the chin and rested on the arm. In the Organological treatise of Praetorius Syntagma Musicum, written in 1618, two separate tunings are given for the Tenor Geige – the instrument which corresponds to the larger tenor violas. One may note that the rib depth is quite substantial; a characteristic trait that would continue in the construction of later tenors far into the 18th Century, some of which will be seen below. These instruments must have been massive. The position of the instrument resting on the arm was likely much more common than one would assume, as ribs depths and corpus most certainly made them difficult to be played under the chin.

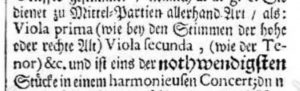

Johann Mattheson’s treatise of 1713, Das Neueröffnette Orchestra, stresses the importance of the separation of alto and tenor parts and of the crucial role violas play in a “harmonious concert”.

It is important to realize that the tenors played a separate role and were occasionally even tuned differently from the smaller, alto instruments. Daniel Hitzler writing in 1623 gives a lower tuning for the tenors by a fifth, separating them entirely.

It is important to realize that the tenors played a separate role and were occasionally even tuned differently from the smaller, alto instruments. Daniel Hitzler writing in 1623 gives a lower tuning for the tenors by a fifth, separating them entirely.

The few real tenors that have miraculously survived can be counted on the fingers. Many of these you may already be aware of, as they are made by familiar names in the history of violin making. Antonio Stradivari, Andrea Guarneri, Jacob Stainer, all produced tenor violas, some of which survive in their original dimensions. A tenor mould marked “TV” survives till the present day in the Stradivari Museum in Cremona. This illustrates the often overlooked fact that these giant tenors were once essential tools for musicians and a rich and important part of our human cultural heritage.

I have long wished to make a comprehensive catalog of all of the surviving tenors, listing not only the rare instruments that have survived in their original states, but also as many as possible those which have been altered and cut down. This is an ongoing task which will continue on this page. The further one looks into the history of the tenor viola, the more multifarious and complex it seems. One sees cut down tenor violas come up for sale at auction quite often; the facts of their lineage and former dimensions going occasionally unmentioned in the catalogs. Below is a short catalog of many rare survivors, starting with the most famous ones which are for the most part unaltered from their original state. I shall also include some violas which have been cut down and attempt to surmise their original dimensions, include playful and fantasy reconstructions of their possible outlines based upon extant examples, as well as include a short history of how the tenor viola developed and subsequently later disappeared from use.

The Stradivari Medici tenor viola

I begin with this instrument as it epitomizes both the rare survival of a large tenor in original condition and the most basic impetus later in history toward the tendency of reduction in size. One may be tempted to think that the first concern and motivation to reduce the corpus of any instrument would be the difference and elimination of part writing for the tenor violas, or perhaps the issue of comfort and playability. The most dominant motivation to butcher such beautiful instruments however was most often financial greed.

This large tenor barely escaped being tragically cut down and is remarkable in its near perfect state of preservation. Why, you might ask, did such atrocious butchery occur? In 1863 the Cherubini’ Conservatory stated that the value of this instrument was only £1,000, most likely because its overly large dimensions made it difficult to play.This valuation gives a window into the 19th C. mindset regarding large tenors. It is remarkable is that the fingerboard and bridge have survived intact. The fact that the most famous violin maker in the world had a tenor mould tells us how common large tenor violas were in the musical culture of 18th Century lutherie.

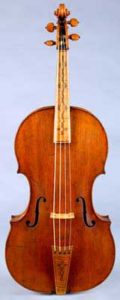

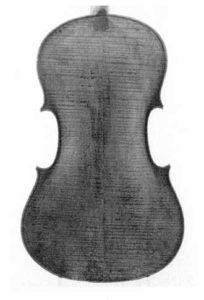

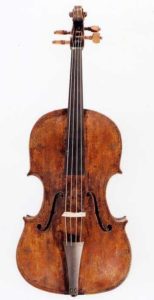

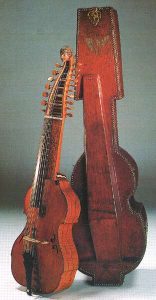

Jakob Stainer, Absam 1650.

The very famous and grand tenor viola has a back of 46cm – the deepest depth of ribs at 44.4cm The viola has a neck of 12.9. which is actually relatively long in comparison to some other tenors. This instrument was made just at the dawn on the invention of wound over gut strings, however almost certainly had all-gut stringing. There are several surviving Stainer tenors and probably many more which have been cut down and lost. One may note that this world famous luthier produced highly arched instruments which held the dominant aesthetic for sound at the time.

The works of German composer Dietrich Buxtehude may help to give us a glimpse into how the large tenors were used in the time of Stainer. Although the viola da gamba often played a primary role independent from the Continuo parts, the alto and tenor clefs were occasionally written in two separate parts, Violas 1 and 2. The middle ranges can however be represented by complex and confusing instrumentation. Most often designated simply with “Violas” (Va) one also sees both viola da braccio, (Vb) or for the Violetta, (Vt) – an instrument which contemporary sources define in differing ways. In BuxWV 4, 24, 34, and 54, two separate viola parts are given which double the violins. It should be noted that while Buxtehude composed during a time when viola da gamba was making its exit from the fashions of the time, he still continued to write parts for that instrument. While I personally know of no direct connection to Stainer, St. Marys Church in Lübeck (where Buxtehude held the position of Organist and Treasurer) had in its possession two tenor violas built by the Lübeck maker Daniel Erich.

The works of German composer Dietrich Buxtehude may help to give us a glimpse into how the large tenors were used in the time of Stainer. Although the viola da gamba often played a primary role independent from the Continuo parts, the alto and tenor clefs were occasionally written in two separate parts, Violas 1 and 2. The middle ranges can however be represented by complex and confusing instrumentation. Most often designated simply with “Violas” (Va) one also sees both viola da braccio, (Vb) or for the Violetta, (Vt) – an instrument which contemporary sources define in differing ways. In BuxWV 4, 24, 34, and 54, two separate viola parts are given which double the violins. It should be noted that while Buxtehude composed during a time when viola da gamba was making its exit from the fashions of the time, he still continued to write parts for that instrument. While I personally know of no direct connection to Stainer, St. Marys Church in Lübeck (where Buxtehude held the position of Organist and Treasurer) had in its possession two tenor violas built by the Lübeck maker Daniel Erich.

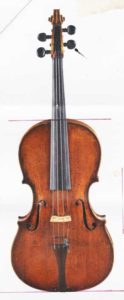

Mathäus Steger Mittersill 1644

Curious and eccentric sound holes, asymmetrical corners and outline characterize this unique German tenor built without a mould. The length of the back at 44.6cm is considerably small in comparison to other German instruments. The ribs are also very slim at 31.8cm, and inlaid into the back plate. This method of building was not uncommon in Germany and one occasionally sees Flemish and Dutch instruments which employ the same method. These instruments usually had linings; Mittersill used the very curious and odd method of gluing cleats or studs to provide ample gluing surface. (See photo below) Another unusual feature is the dramatic slant of the bass bar position running across the grain. This positioning would have limited the mensur or bridge placement considerably. The instrument well illustrates the acuity of experimentation in early mid-17th Century violas.

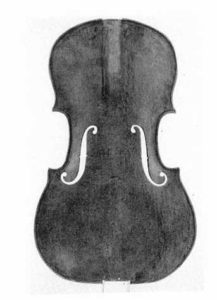

Andrea Guarneri 1664

The grandfather of Joseph Guerneri del Gesu, Andrea Guarneri began studying in the famous Amati workshop at the age of 10 years old. This giant tenor is well known among viola geeks as it truly is a monster instrument. The bouts of the viola are so wide that wings were added to the 2-piece spruce table. The 48.2cm back is large by any standard of viola, however what is most remarkable is that the neck is quite long at 15.5cm, very unusual for an Italian tenor, whose necks are often shorter. It is nothing short of a miracle that this tenor has survived in such a remarkably perfect state of preservation. Worm damage was repaired in the 1940’s in the Bisach workshop; the nails were removed and carefully replaced with wooden dowels.

Gaspar Borbon 1692

Gaspar Borbon worked from around 1673-1705 and many of his instruments, (as well as his pupil Egidius Snoeck) survive today and are housed in the Koninklijke Musea voor Kunst en Geschiedenis, Brussels. While Brescian instruments appear to have commonly inspired this Flemish maker, this beautiful tenor with its upright, straight sound holes appears to pay homage to the Stainer/Amati tradition.

Hauteur: 72,5 cm, Largeur: 26,8 cm, Profondeur: 11 cm

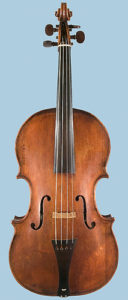

The Gasparo Da Salo Tenor Violas

There are no less than 10 uncut tenor violas attributed to Gasparo da Salo, and I hope to make a complete catalog of these in the near future. One should also take some attributions carefully and with a grain of salt. Brescian instruments are the most common subjects of forgeries as their characteristics tended to attract the forgers muse. Inevitably any viola which looked as if made in this neighboring city to Cremona, would magically have a Da Salo label put inside. This Brescian master tended to make larger instruments as opposed to his student Paolo Maggini. This grand tenor retains it original dimensions, with a neck length of 12.3

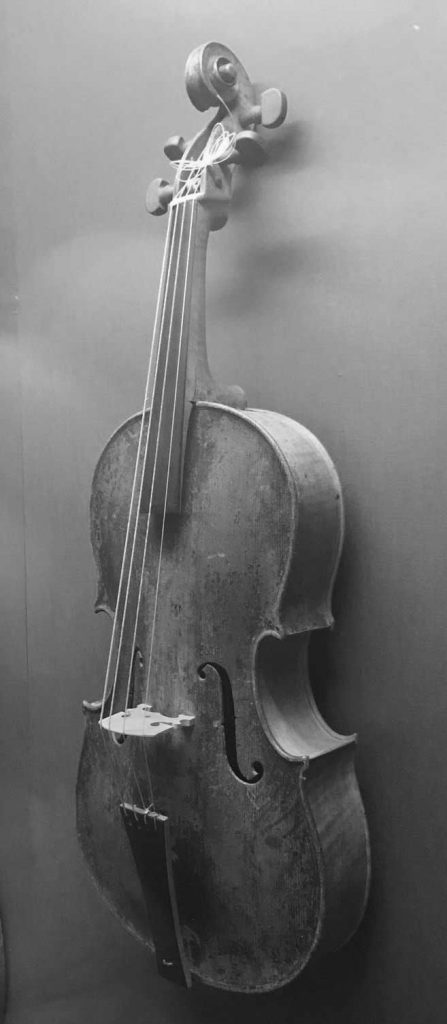

Johann Michael Alban. Bozen or Salzburg 1707

This giant tenor with a corpus of 45cm is particularly interesting as the extremely deep ribs of bring into question the division between large tenor and violoncello piccolo. One notes that the neck is long in comparison to the Italian tenors. I have made a copy of this instrument and found that it can be played both under the chin and resting on the arm comfortably.

On first appearance when walking into the treasure trove of instruments housed in the Kunsthistorische Museum in Vienna this massive tenor tends to lead one to think it was a one-off experiment. Ribs of such depth also magnify in the mind the modern misconception of unplayability and whisper of their miraculous survival.

Hanging imprisioned behind glass, one gets a strong sense of the existence of a true chimerical survivor. My personal belief is that far from being an experiment, ribs and corpus of such magnitude were much more common than is normally believed, especially on instruments made in Germany, Austria, and the Northern Alpine region. RIb depth is actually one of the most common things to be altered in an instrument. In the case of the violoncello, the depths of ribs are expanded for more air volume, transversely with tenor violas the ribs are commonly shorted to allow more comfortable playing under the chin.

Oddities in the world of lutherie and Organology abound. The absence of surviving tenors with ribs as deep as the Alban viola does not necessarily mean that many were not built, or that Johann Michael working even at the comparatively later date of 1707 was a particular maverick in making successful experiments in sound. Other instruments though rare do exist, and were not early curiosities; instead being instruments likely produced to the demands of real musicians. This brings us to the next German tenor.

Anon. German Tenor Viola ca. 1700 or later.

The Germanische Museum in Nurenberg have this cataloged as a 17th C. instrument. It is however quite obvious to me that this viola was built much later, possibly even as late as 1750. The high rib depths recall the Alban Tenor of 1707 above. Tenor violas with cello-like ribs seem to be more common in Germany and Tyrol than in Italy, England, or other centers of lutherie. One may also note that the neck is quite long (I will provide dimensions later) similar to the Alban tenor. Such anomalies with ribs so deep as to confuse the line between piccolo cello and tenor viola inevitably lead one to question the historical playing position. While the Alban copy I made is surprising easy to play “under the chin” its more likely that these instruments were played rested on the arm. While this is hardly a playing posture suited to virtuosity, it is certainly manageable when one becomes accustomed to the posture.

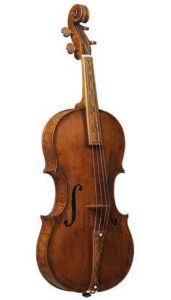

Barack Norman Grand Tenor

This wonderful grand tenor viola made in the period of 1700-1710 defies normal classifications due to the back folds on both bouts. Carved, arched backs with a top fold can be found mostly on Cremonese and Northern Italian viola da gambas and other bass instruments. The rib depth at the corners is an astonishing 72mm. Norman’s experimentation with this large tenor using gamba construction for the back allowed him to employ a second fold at the lower bout.

The depth here at 14mm leaves no doubt as to the playing posture intended; this was a giant tenor meant to be played under the chin. One should understand that this method of construction was not common, however illustrates well that there was a general desire for larger tenor sized instruments.

This lovely instrument is in the private collection of Benjamin Hebbert in London, who has kindly provided me with the following dimensions: 472mm length (of front) – 72mm rib depth at corners- 48mm rib depth at heel – 14 – fourteen mm at endpin – 244 / 157 / 278 mm widths – 44cm string length. Ben has written an extensive blog entry on this instrument which is a true pleasure to read. One may also hear audio samples of it being played by Paul Silverthorne.

Baroque Tenor Viola by Jonas Heringer Füssen, 1625

The long corners and double purfling take Brescian instruments as inspiration in this lovely tenor made in Tyrol. The instrument would have been originally fitted with all-gut strings. I include it here as it is a fine example of an early 17th Century tenors. Further research is needed on my part; a trip to the Tiroler Landesmuseum Ferdinandeum is pending, should I have time in the near future.

Anonymous Tenor, Austria ca. 1700

This interesting viola in the second image below came up for auction in 2014 at the Dorotheum in Vienna Austria and was listed as an anonymous cut down tenor with a corpus of 43.4cm. Based upon comparison of later Alban family outlines, sound holes and body dimensions I believe the original to have been quite large at 45-50cm and quite possibly made by Johann Michael Alban, son of Mathias Alban. What you see below is my own fantasy recreation based carefully upon outlines of several instruments from this school of lutherie.

March 2018: I will adding additional instruments in the coming months should time allow me to do so. In the future I will also begin to arrange this as a catalog in chronological order and provide a table which compares by region, compositions during their time of creations, and dimensions, when possible. I would also greatly appreciate your comments, suggestions, and images of additional instruments. I am hoping that this blog can help to dispel some of the myths regarding large tenors, and bring forth more interest in performing on them. Stay tuned.

Thankfully, the instrument survives in a remarkable undamaged state, including its charming original case of red leather, in the Hugarian National Museum.

Thankfully, the instrument survives in a remarkable undamaged state, including its charming original case of red leather, in the Hugarian National Museum.